Burnley Men in Prison Camp Mutiny

Two men from Burnley - Albert

Uttley 7859 1st East Lancs Regiment (who became a Prisoner of War on 31st

August 1914) and Fred Chaffer 9677

2nd Kings Own Royal Lancaster Regiment (who became a PoW on 8th May 1915)

– were being held at the Bokelah Prisoner of War Camp when a mutiny broke

out on 26 May 1916, Conditions at all POW camps were harsh, compounded by the

shortage of food and supplies. Prisoners were issued a uniform supplied by the

Red Cross, which was black with brown stripes down the legs and a brown insert

in the sleeves of the jacket. The meagre food rations consisted of black bread

and soup. The men were dependent on packages from home or the Red Cross for

additional food, money and supplies. Many men were used as labour in the salt

or tin mines and many soldiers perished durin enforced confinement.

The Bokelah mutiny flared when twenty-eight hungry ‘British’

prisoners who had been laying rails for the railway learned that their hours

of labour were to be extended. They refused to work and were set upon by the

German guards. The POW’s, including eight Canadians, were put on trial

accused of causing a military disturbance and were all sentenced to 10 years

hard labour.

The ringleader was deemed to be Francis Armstrong of the 13th CanadianBattalion,

who was sentenced to death. His sentence was later commuted to 12 years hard

labour whilst the others had theirs increased to 12 years.

The above account has based on an article written by Adrian Watkinson and Diana Beaupre “Walter Fuller’s War” which appeared in the Western Front Journal “Stand To” number 93 December2011/2012.

Further information from Adrian and Diana appears below:- (including

transcripts from the trial)

The punishments meted out by the Germans were directly responsible

for the death of one Canadian involved in the mutiny. Private William Brooke

from Ottawa, died of pneumonia on 13 March 1917 whilst in the Cologne Fortress.

He was initially buried in Sudfriedhof but his body was the n moved to Brussels

Town Cemetery in 1919.

Francis Armstrong survived the war and was released from captivity on 6 January

1919 when he returned to England. Because of his weakened state, he succumbed

to influenza and died on 23 May 1919. He is buried in Orpington All Saints Church

Cemetery, Kent.

Many years later in 1932, Private Walter Fuller

was able to give his account of the circumstances for the mutiny at a sitting

of the National Reparations Committee in the Macdonald Hotel at Edmonton,Alberta,Canada.

The purpose of the Committee was to hear claims filed by ex-prisoners of war

who were suffering a ‘present disability’ resulting from maltreatment.

He described how one day, the men had been required to lay heavy track for moving

fertiliser. When a man wanted to rest, he was knocked

down by a guard. The group of about 28 men were later marched back to camp.

He continued: The guards refused to give the prisoners dinner and ordered them

to go back to work without eating. One prisoner called Armstrong, who could

speak German, stepped out in front and asked the sergeant if we could see the

camp commandant to make a complaint. The sergeant said the commandant was away,

although we could plainly see him 200 yards away. Then the sergeant called out

the guard and said if we didn’t move at the count of three, he would order

them to shoot. We started towards the gate with the Germans rushing at us. As

we passed through the gate, an old man called Logan of the Northumberland Fusiliers,

who was the last man through, was bayoneted through the back by the guard on

gate duty. This guard was simply on post at the gate and not called to rush

us like the others. The Germans called it a mutiny to cover up the killing of

Logan and we were all court- martialed. Armstrong was at first sentenced to

be shot, but his sentence was commuted. The rest of us were all taken to the

military fortress prison of Neu Koln. Conditions were so bad here that I got

dysentery. After some months of this jail term, the party was released following

the daring escape of a British guardsman, who told of the conditions in the

jail to authorities in the old country. As a result of representations made

through a neutral power, the men were all sent to a prison camp near the Kiel

canal, where they were put to work unloading freighters from Scandanavia.

The same Committee heard further evidence from Walter about an incident which

happened some months later at Wilhemshafen in Germany; One morning in October,

I think, a German came along and asked if the Canadians 21

wanted a bath. Then we were formed up outside and told to strip. We did, as

we were glad to have the chance of getting a bath. Instead of taking us for

a bath, the guards fixed bayonets and marched us to a field where some Russians

had been cutting sods. We were told to pick up the sods and carry them from

one end of the field to the other. This went on from 1.30 to about 3.30 or 4.00.

Just to amuse the guards. (Edmonton Journal, 3 Oct 1932)

On his release at the end of the war, Walter’s physical condition was

described by Army doctors at Seaford in East Sussex as ‘had influenza,

weak from poor food, hard work and irrigation work on moors’ (Medical

History of an Invalid 8 Apr 1919). Walter told the Committee he had suffered

from neurasthemia [severe mental and physical fatigue] and bronchitis since

being in the German prisons. Walter was repatriated to Ripon in Yorkshire on

26 December 1918 and returned to the family home at 62 St Michael’s Street,

Folkestone on 29 December 1918. Accompanied by Charles Fuller his father, Walter

attended the meeting of Folkestone Town Council on Wednesday 1 January 1919

and expressed his thanks for the parcels which were sent to him from the town.

He said the food which was given to him he could not eat and it was the parcels

which kept him alive. He was engaged in irrigation work, often with water up

to his knees, and made to work twelve hours a day. They had coffee in the morning

and watery

soup for dinner, twelve cabbages being boiled in a big vessel for 1,000 men.

Whilst in prison, they received no parcels, and when he came out, there were

75 parcels awaiting him. The Mayor thanked Mr Fuller and his son, and wished

them a Happier New Year (applause).

(FHSC Herald, 4 Jan 1919)

Walter returned to Canada on the SS Cassandra almost six years to the day after

first setting off for Canada and he was demobilised from war service in Edmonton,

Alberta. The reason for discharge on 18 May 1919 was stated as ‘medically

unfit’.(National Archives,Canada) He was still only 23 years of age.

![]()

![]()

![]() The

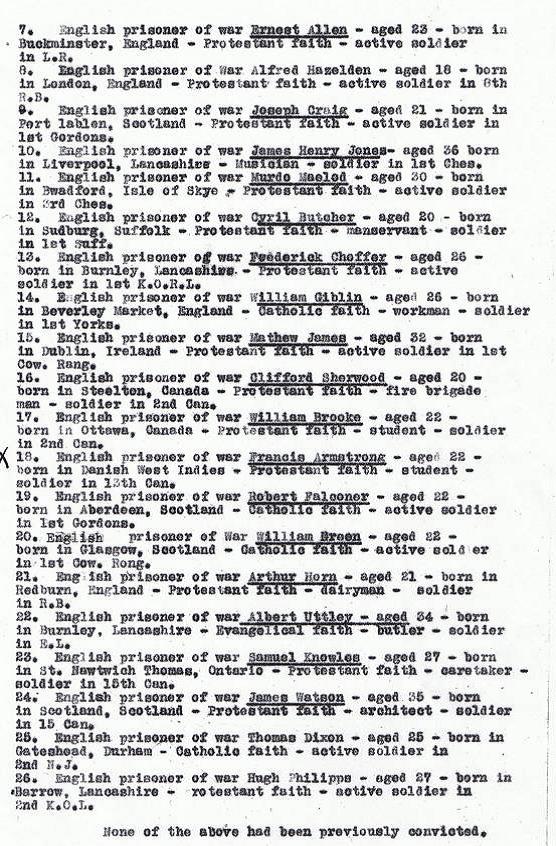

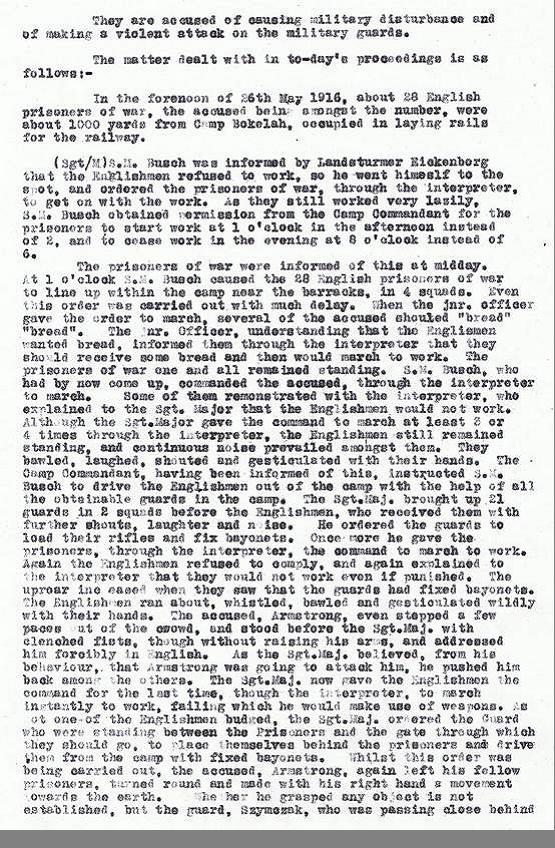

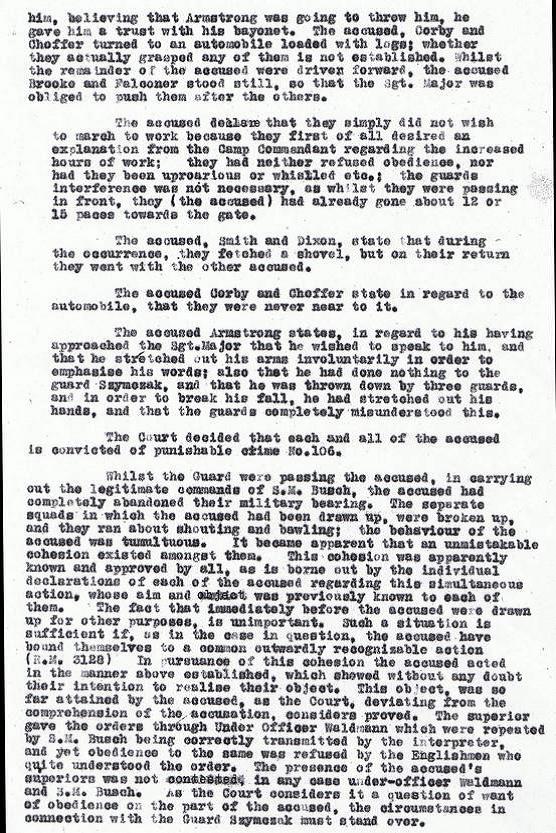

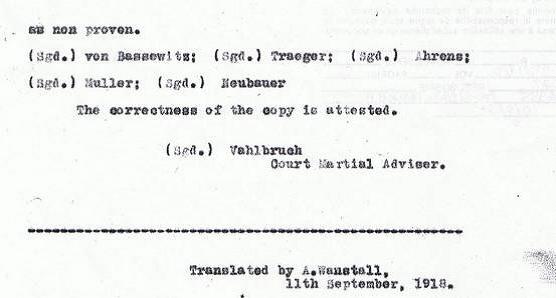

following document is a translated copy of the Court Martial proceedings:

The

following document is a translated copy of the Court Martial proceedings: